Tic Tac Toe

Introduction

Let’s learn how we can code tic-tac-toe! While creating TTT, you’ll learn quite a lot about what goes on behind the scenes of any game you play. Here are some of the concepts you will learn or review:

- Simple game design

- Python’s ternary operator, which looks like

min = a if a < b else b - Multi-dimensional arrays (matrices)

- Break and continue

For this side quest, you are provided a skeleton of a working implementation of TTT, with the following functions:

- main()

- tic_tac_toe()

- check_win()

- display_TTT()

You are also provided a solution to look at in case you get stuck. This side quest isn’t graded and is purely for fun and learning, so please work through everything yourself! Lastly, if you run into any issues, email Jesse (jessew13@email.unc.edu)!

Basics:

Let’s learn the basics of multi-dimensional arrays in Python. Given this code: matrix = [[0, 1, 2], [3, 4, 5], [6, 7, 8]], you can think of matrix as 3 lists of 3 elements each or a 3x3 grid of elements.

[0 1 2] [3 4 5] [6 7 8]

Visually, the element in row 0, column 0 is 0. The element in row 2, column 1 is 7. So matrix[0][0] returns 0. matrix[2][1] returns 7.

In terms of code, it’s a list of 3 lists. So matrix[0] returns [0, 1, 2]. If we index this list at 0, we get 0. These are 2 ways of thinking about the same concept. Do you see how matrices might be useful for coding TTT?

Step 0:

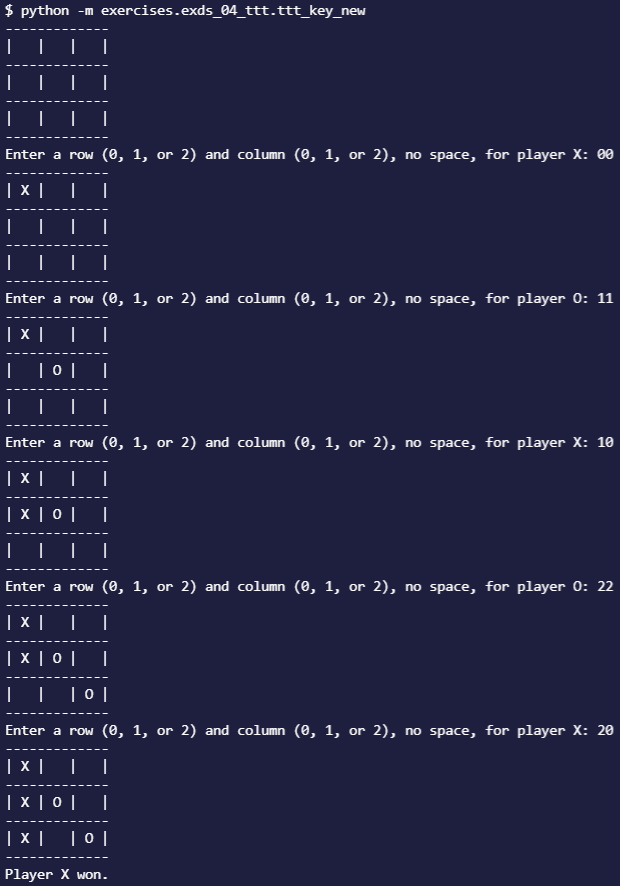

Here’s sample output from the key provided.  Each turn, the board is displayed, and the player inputs matrix indices as a two-digit string without spaces.

Each turn, the board is displayed, and the player inputs matrix indices as a two-digit string without spaces.

Now familiarize yourself with the skeleton code provided. What’s especially important is how the TTT BOARD is set up. It’s a global 3x3 matrix that is initially filled with CHARS[0], which is just 3 whitespaces. If, for example, player X puts an X in the bottom right corner, with indices (i, j) == (2, 2), then we would want to run this code: BOARD[2][2] = CHARS[1]

Step 1:

Set player_name to “X” if num_turns is odd, else set it to “O” if num_turns is even. Use Python’s ternary operator to do so.

Step 2:

Determine what i and j, the indices of the board, should be based on player_input.

Step 3:

Update the board to have the correct value (based on what player_name is) at indices (i, j). Then display the board.

Step 4:

Take a look at check_win()’s signature and docstring to see how it’s meant to work. Assuming that it functions as intended now (you could skip to steps 6-8 to actually implement it now), write some code to check if the piece placed at indices (i, j) caused a win.

If there is, in fact, a winner, do we break or continue the loop?

Step 5:

Check for a draw. If there is a draw, should we break or continue?

Step 6:

Check for a win in the row of element (i, j) of BOARD. The solution hard codes instead of using a loop, but you should definitely attempt to use a loop for this!

Step 7:

Check for a win in the column of element (i, j) of BOARD.

Step 8:

Check the diagonals for a win.

Step 9:

Implement display_TTT() to display the board.

OPTIONAL:

- Under step 2, after player input, you should check that the space the player chose is empty. Of course, players can’t overwrite each other’s pieces in TTT.

- During step 4, you may also

raisean error if a player attempts to use an already filled space. Which Python error is most relevant? You may need to Google the types of built-in exceptions in Python. - Notice the order of steps 1-5 and the optional step. Reason about why each line of code is placed where it is instead of somewhere else. For example, why should we increment num_turns after step 3? Why can we display the board at the end of step 3?

CHALLENGE:

- This game can be generalized to an N-dimensional board, with N an

intthe player gets to choose. For an N-dimensional TTT game, you would want, at minimum, an N x NBOARDwith acheck_win()that works in N dimensions. Note that for any dimensions, elements on the main diagonal (top left to bottom right) always havei == jand elements on the off diagonal (top right to bottom left) havei + j == N - 1.display_TTT()was really hard to implement just for 3D, so you can try play without displaying the board or find some clever way to implement the display using just text. To be frank, it’d probably be easier to learn and use a Python GUI library to display the board.